Boat Building

The Romans were not natural boat builders. In fact Roman boat building was a bit of a copycat exercise. Most early designs were copied from captured Phoenician ships. But not having the ideas themselves didn’t prevent the Romans from doing them better and Roman ships soon grew to control most of the Mediterranean.

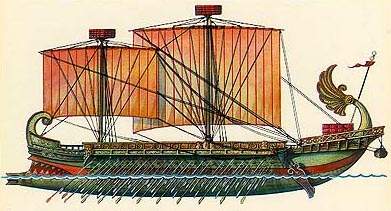

Ships were built without written plans. Instead craftsmen relied on a long apprenticeship, picking up skills that were passed down through generations. For this reason master ship-builders could grow wealthy if they were able to put large numbers of ships out of their yards. Roman ships had no rudder, which was only invented in the medieval times. Instead they were steered with two oars that dragged behind the boat to port and starboard. Sails were made of either thick linen or animal skins. Sometimes they were tinted with dyes. Wood was the main ingredient in the recipe for a Roman ship as well as Iron, which was used to secure the wood together and often to plate the hull of warships to defend against the enemy. Pitch was also used to create a watertight seal.

While warships tended to be comparatively small to allow for maneuverability, goods ships could be huge, and would have round hulls to allow for greater cargo. Ships would carry hugely construction materials such as marble and iron so they needed to be strong. Merchant ships would also use sails rather than oars. The masts held a single sail on two curved beams. Oars were still used for steering purposes.

The Romans were not natural boat builders. In fact Roman boat building was a bit of a copycat exercise. Most early designs were copied from captured Phoenician ships. But not having the ideas themselves didn’t prevent the Romans from doing them better and Roman ships soon grew to control most of the Mediterranean.

Ships were built without written plans. Instead craftsmen relied on a long apprenticeship, picking up skills that were passed down through generations. For this reason master ship-builders could grow wealthy if they were able to put large numbers of ships out of their yards. Roman ships had no rudder, which was only invented in the medieval times. Instead they were steered with two oars that dragged behind the boat to port and starboard. Sails were made of either thick linen or animal skins. Sometimes they were tinted with dyes. Wood was the main ingredient in the recipe for a Roman ship as well as Iron, which was used to secure the wood together and often to plate the hull of warships to defend against the enemy. Pitch was also used to create a watertight seal.

While warships tended to be comparatively small to allow for maneuverability, goods ships could be huge, and would have round hulls to allow for greater cargo. Ships would carry hugely construction materials such as marble and iron so they needed to be strong. Merchant ships would also use sails rather than oars. The masts held a single sail on two curved beams. Oars were still used for steering purposes.

There is also evidence in the latter half of the Roman period for lavishly decorated ships designed to show the wealth and prestige of their owner. Ivory, copper, marble and clay were used for decoration and sometimes even silver and gold. While most ships were quite small, these huge ships were built with space inside for guests to sleep and dine—much like the modern day cruise liner! The emperor Caligula built even built a floating palace that was found at Lake Nemi.

All ships would have a wooden figure at the prow and stern. The one at the prow was the figure that gave the ship its name. The one at the stern was the god who would protect the boat. Ships were commonly named after either gods or if they were warships famous Roman victories. Over the course of the empire Roman shipyards produced huge numbers of ships both for war and for transporting goods.

There were some crucial innovations during the Roman period. One of the most infamous Roman inventions was the “raven” or “corvus” in Latin. It was a portable bridge with a spike in the far end that could be dropped against an enemy vessel and allow the Roman marines to rush the enemy boat. This tactic essentially turned a sea battle into a land battle. This was a wise tactic for the Romans to pursue with their long-standing proficiency on land. This tactic was first used off Mylae in the war against Carthage. Other innovations in Roman ship building include, metal plating the hulls; developing mechanisms such as cog-wheels and revolving platforms; the use of hydraulics to pump water; and the equipment such as anchors and steering devices.

It was crucial for a shipyard to be able to launch a ship after it was built, particularly if the ship was large. Various options were used. Some ship-builders constructed a huge cradle that would then be pulled into the water. Others dug a trench underneath the ship and mounted the ship on skids, the sea could be let into what was effectively a new harbor and float the ship up and away! There was a famous shipyard at Stifone (Narni) in modern day Umbria, that relied on the navigable Nera river. The shipyard was built around an artificial channel carved into rock. It was nearly three hundred meters long and linked via channels to the Nera river. Props were laid across the channel to support ships as they were constructed. The Umbrian woodland would have offered a lot of timber for construction. The constructed ships could be sailed through the channels up the river and on to the sea.

All ships would have a wooden figure at the prow and stern. The one at the prow was the figure that gave the ship its name. The one at the stern was the god who would protect the boat. Ships were commonly named after either gods or if they were warships famous Roman victories. Over the course of the empire Roman shipyards produced huge numbers of ships both for war and for transporting goods.

There were some crucial innovations during the Roman period. One of the most infamous Roman inventions was the “raven” or “corvus” in Latin. It was a portable bridge with a spike in the far end that could be dropped against an enemy vessel and allow the Roman marines to rush the enemy boat. This tactic essentially turned a sea battle into a land battle. This was a wise tactic for the Romans to pursue with their long-standing proficiency on land. This tactic was first used off Mylae in the war against Carthage. Other innovations in Roman ship building include, metal plating the hulls; developing mechanisms such as cog-wheels and revolving platforms; the use of hydraulics to pump water; and the equipment such as anchors and steering devices.

It was crucial for a shipyard to be able to launch a ship after it was built, particularly if the ship was large. Various options were used. Some ship-builders constructed a huge cradle that would then be pulled into the water. Others dug a trench underneath the ship and mounted the ship on skids, the sea could be let into what was effectively a new harbor and float the ship up and away! There was a famous shipyard at Stifone (Narni) in modern day Umbria, that relied on the navigable Nera river. The shipyard was built around an artificial channel carved into rock. It was nearly three hundred meters long and linked via channels to the Nera river. Props were laid across the channel to support ships as they were constructed. The Umbrian woodland would have offered a lot of timber for construction. The constructed ships could be sailed through the channels up the river and on to the sea.

George C.V. Holmes, ‘Ancient and Modern Ships’

As accessed via Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/33098

CHAPTER II.

ANCIENT SHIPS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN AND RED SEAS.

It is not difficult to imagine how mankind first conceived the idea of making use of floating structures to enable him to traverse stretches of water. The trunk of a tree floating down a river may have given him his first notions. He would not be long in discovering that the tree could support more than its own weight without sinking. From the single trunk to a raft, formed of several stems lashed together, the step would not be a long one. Similarly, once it was noticed that a trunk, or log, could carry more than its own weight and float, the idea would naturally soon occur to any one to diminish the inherent weight of the log by hollowing it out and thus increase its carrying capacity; the subsequent improvements of shaping the underwater portion so as to make the elementary boat handy, and to diminish its resistance in the water, and of fitting up the interior so as to give facilities for navigating the vessel and for accommodating in it human beings and goods, would all come by degrees with experience. Even to the present day beautiful specimens exist of such boats, or canoes, admirably formed out of hollowed tree-trunks. They are made by many uncivilized peoples, such as the islanders of the Pacific and some of the tribes of Central Africa. Probably the earliest type of _built-up_ boat was made by stretching skins on a frame. To this class belonged the coracle of the Ancient Britons, which is even now in common use on the Atlantic seaboard of Ireland. The transition from a raft to a flat-bottomed boat was a very obvious improvement, and such vessels were probably the immediate forerunners of ships.

It is usual to refer to Noah's ark as the oldest ship of which there is any authentic record. Since, however, Egypt has been systematically explored, pictures of vessels have been discovered immensely older than the ark--that is to say, if the date usually assigned to the latter (2840 B.C.) can be accepted as approximately correct; and, as we shall see hereafter (p. 25), there are vessels _now in existence in Egypt which were built_ about this very period. The ark was a vessel of such enormous size that the mere fact that it was constructed argues a very advanced knowledge and experience on the part of the contemporaries of Noah. Its dimensions were, according to the biblical version, reckoning the cubit at eighteen inches; length, 450 feet; breadth, 75 feet; and depth, 45 feet. If very full in form its "registered tonnage" would have been nearly 15,000. According to the earlier Babylonian version, the depth was equal to the breadth, but, unfortunately, the figures of the measurements are not legible.

It has been sometimes suggested that the ark was a huge raft with a superstructure, or house, built on it, of the dimensions given above. There does not, however, appear to be the slightest reason for concurring with this suggestion. On the contrary, the biblical account of the structure of the ark is so detailed, that we have no right to suppose that the description of the most important part of it, the supposed raft, to which its power of floating would have been due, would have been omitted. Moreover, the whole account reads like the description of a ship-shaped structure.

[…]

SHIPBUILDING IN ANCIENT GREECE AND ROME.

In considering the history of the development of shipbuilding, we cannot fail to be struck with the favourable natural conditions which existed in Greece for the improvement of the art. On the east and west the mainland was bordered by inland seas, studded with islands abounding in harbours. Away to the north-east were other enclosed seas, which tempted the enterprise of the early navigators. One of the cities of Greece proper, Corinth, occupied an absolutely unique position for trade and colonization, situated as it was on a narrow isthmus commanding two seas. The long narrow Gulf of Corinth opening into the Mediterranean, and giving access to the Ionian Islands, must have been a veritable nursery of the art of navigation, for here the early traders could sail for long distances, in easy conditions, without losing sight of land. The Gulf of Ægina and the waters of the Archipelago were equally favourable. The instincts of the people were commercial, and their necessities made them colonizers on a vast scale; moreover, they had at their disposal the experience in the arts of navigation, acquired from time immemorial, by the Egyptians and Phoenicians. Nevertheless, with all these circumstances in their favour, the Greeks, at any rate up to the fourth century B.C., appear to have contributed nothing to the improvement of shipbuilding.[8] The Egyptians and Phoenicians both built triremes as early as 600 B.C., but this class of vessel was quite the exception in the Greek fleets which fought at Salamis 120 years later.

The earliest naval expedition mentioned in Greek history is that of the allied fleets which transported the armies of Hellas to the siege of Troy about the year 1237 B.C. According to the Greek historians, the vessels used were open boats, decks not having been introduced into Greek vessels till a much later period.

The earliest Greek naval battle of which we have any record took place about the year 709 B.C., over 500 years after the expedition to Troy and 1,000 years after the battle depicted in the Temple of Victory at Thebes. It was fought between the Corinthians and their rebellious colonists of Corcyra, now called Corfu.

Some of the naval expeditions recorded in Greek history were conceived on a gigantic scale. The joint fleets of Persia and Phoenicia which attacked and conquered the Greek colonies in Ionia consisted of 600 vessels. This expedition took place in the year 496 B.C. Shortly afterwards the Persian commander-in-chief, Mardonius, collected a much larger fleet for the invasion of Greece itself.

After the death of Cambyses, his successor Xerxes collected a fleet which is stated to have numbered 4,200 vessels, of which 1,200 were triremes. The remainder appears to have been divided into two classes, of which the larger were propelled with twenty-five and the smaller with fifteen oars a-side. This fleet, after many misfortunes at sea, and after gaining a hard-fought victory over the Athenians, was finally destroyed by the united Greek fleet at the ever-famous battle of Salamis. The size of the Persian monarch's fleet was in itself a sufficient proof of the extent of the naval power of the Levantine states; but an equally convincing proof of the maritime power of another Mediterranean state, viz., Carthage, at that early period--about 470 B.C.--is forthcoming. This State equipped a large fleet, consisting of 3,000 ships, against the Greek colonies in Sicily; of these 2,000 were fighting galleys, and the remainder transports on which no less than 300,000 men were embarked. This mighty armada was partly destroyed in a great storm. All the transports were wrecked, and the galleys were attacked and totally destroyed by the fleets of the Greek colonists under Gelon on the very day, according to tradition, on which the Persians were defeated at Salamis. Out of the entire expedition only a few persons returned to Carthage to tell the tale of their disasters.

The foregoing account will serve to give a fair idea of the extent to which shipbuilding was carried on in the Mediterranean in the fifth century before the Christian era.

We have very little knowledge of the nature of Greek vessels previously to 500 B.C. Thucydides says that the ships engaged on the Trojan expedition were without decks.

According to Homer, 1,200 ships were employed, those of the Boeotians having 120 men each, and those of Philoctetes 50 men each. Thucydides also relates that the earliest Hellenic triremes were built at Corinth, and that Ameinocles, a Corinthian naval architect, built four ships for the Samians about 700 B.C.; but triremes did not become common until the time of the Persian War, except in Sicily and Corcyra (Corfu), in which states considerable numbers were in use a little time before the war broke out.

British Museum, which was found at Vulci in Etruria. It is one of the very few representations now in existence of ancient Greek biremes. It gives us far less information than we could wish to have. The vessel has two banks of oars, those of the upper tier passing over the gunwale, and those of the lower passing through oar-ports. Twenty oars are shown by the artist on each side, but this is probably not the exact number used. Unfortunately the rowers of the lower tier are not shown in position. The steering was effected by means of two large oars at the stern, after the manner of those in use in the Egyptian ships previously described. This is proved by another illustration of a bireme on the same vase, in which the steering oars are clearly seen. The vessel had a strongly marked forecastle and a ram fashioned in the shape of a boar's head. It is a curious fact that Herodotus, in his history (Book III.), mentions that the Samian ships carried beaks, formed to resemble the head of a wild boar, and he relates how the Æginetans beat some Samian colonists in a sea-fight off Crete, and sawed off the boar-head beaks from the captured galleys, and deposited them in a temple in Ægina. This sea-fight took place about the same time that the vases were manufactured, from which Figs. 8 and 9 are copied. There was a single mast with a very large yard carrying a square sail. The stays are not shown, but Homer says that the masts of early Greek vessels were stayed fore and aft.

It is impossible to say whether this vessel was decked. According to Thucydides, the ships which the Athenians built at the instigation of Themistocles, and which they used at Salamis, were not fully decked. That Greek galleys were sometimes without decks is proved by Fig. 10, which is a copy of a fragment of a painting of a Greek galley on an Athenian vase now in the British Museum, of the date of about 550 B.C. It is perfectly obvious, from the human figures in the galley, that there was no deck. Not even the forecastle was covered in. The galleys of Figs. 8 and 9 had, unlike the Phoenician bireme of Fig. 7, no fighting-deck for the use of the soldiers. There was also no protection for the upper-tier rowers, and in this respect they were inferior to the Egyptian ship shown in Fig. 6. It is probable that Athenian ships at Salamis also had no fighting, or flying decks for the use of the soldiers; for, according to Thucydides, Gylippos, when exhorting the Syracusans, nearly sixty years later, in 413 B.C., said, "But to them (the Athenians) the employment of troops on deck is a novelty." Against this view, however, it must be stated that there are now in existence at Rome two grotesque pictures of Greek galleys on a painted vase, dating from about 550 B.C., in which the soldiers are clearly depicted standing and fighting upon a flying deck. Moreover, Thucydides, in describing a sea-fight between the Corinthians and the Corcyreans in 432 B.C., mentions that the decks of both fleets were crowded with heavy infantry archers and javelin-men, "for their naval engagements were still of the old clumsy sort." Possibly this last sentence gives us a clue to the explanation of the apparent discrepancy. The Athenians were, as we know, expert tacticians at sea, and adopted the method of ramming hostile ships, instead of lying alongside and leaving the fighting to the troops on board. They may, however, have been forced to revert to the latter method, in order to provide for cases where ramming could not be used; as, for instance, in narrow harbours crowded with shipping, like that of Syracuse.

It is perfectly certain that the Phoenician ships which formed the most important part of the Persian fleet at Salamis carried fighting-decks. We have seen already (p. 28) that they used such decks in the time of Sennacherib, and we have the distinct authority of Herodotus for the statement that they were also employed in the Persian War; for, he relates that Xerxes returned to Asia in a Phoenician ship, and that great danger arose during a storm, the vessel having been top-heavy owing to the deck being crowded with Persian nobles who returned with the king.

In addition to the triremes, of which not a single illustration of earlier date than the Christian era is known to be in existence, both Greeks and Persians, during the wars in the early part of the fifth century B.C., used fifty-oared ships called penteconters, in which the oars were supposed to have been arranged in one tier. About a century and a half after the battle of Salamis, in 330 B.C., the Athenians commenced to build ships with four banks, and five years later they advanced to five banks. This is proved by the extant inventories of the Athenian dockyards. According to Diodoros, they were in use in the Syracusan fleet in 398 B.C. Diodoros, however, died nearly 350 years after this epoch, and his account must, therefore, be received with caution.

The evidence in favour of the existence of galleys having more than five superimposed banks of oars is very slight.

Alexander the Great is said by most of his biographers to have used ships with five banks of oars; but Quintus Curtius states that, in 323 B.C., the Macedonian king built a fleet of seven-banked galleys on the Euphrates. Quintus Curtius is supposed by the best authorities to have lived five centuries after the time of Alexander, and therefore his account of these ships cannot be accepted without question.

It is also related by Diodoros that there were ships of six and seven banks in the fleet of Demetrios Poliorcetes at a battle off Cyprus in 306 B.C., and that Antigonos, the father of Poliorcetes, had ships of eleven and twelve banks. We have seen, however, that Diodoros died about two and a half centuries after this period. Pliny, who lived from 61 to 115 A.D., increases the number of banks in the ships of the opposing fleets at this battle to twelve and fifteen banks respectively. It is impossible to place any confidence in such statements.

Theophrastus, a botanist who died about 288 B.C., and who was therefore a contemporary of Demetrios, mentions in his history of plants that the king built an eleven-banked ship in Cyprus. This is one of the very few contemporary records we possess of the construction of such ships. The question, however, arises, Can a botanist be accepted as an accurate witness in matters relating to shipbuilding? The further question presents itself, What meaning is intended to be conveyed by the terms which we translate as ships of many banks? This question will be reverted to hereafter.

In one other instance a writer cites a document in which one of these many-banked ships is mentioned as having been in existence during his lifetime. The author in question was Polybios, one of the most painstaking and accurate of the ancient historians, who was born between 214 and 204 B.C., and who quotes a treaty between Rome and Macedon concluded in 197 B.C., in which a Macedonian ship of sixteen banks is once mentioned. This ship was brought to the Tiber thirty years later, according to Plutarch and Pliny, who are supposed to have copied a lost account by Polybios. Both Plutarch and Pliny were born more than two centuries after this event. If the alleged account by Polybios had been preserved, it would have been unimpeachable authority on the subject of this vessel, as this writer, who was, about the period in question, an exile in Italy, was tutor in the family of Æmilius Paulus, the Roman general who brought the ship to the Tiber.

The Romans first became a naval power in their wars with the Carthaginians, when the command of the sea became a necessity of their existence. This was about 256 B.C. At that time they knew nothing whatever of shipbuilding, and their early war-vessels were merely copies of those used by the Carthaginians, and these latter were no doubt of the same general type as the Greek galleys. The first Roman fleet appears to have consisted of quinqueremes.

The third century B.C. is said to have been an era of gigantic ships. Ptolemy Philadelphos and Ptolemy Philopater, who reigned over Egypt during the greater part of that century, are alleged to have built a number of galleys ranging from thirteen up to forty banks. The evidence in this case is derived from two unsatisfactory sources. Athenæos and Plutarch quote one Callixenos of Rhodes, and Pliny quotes one Philostephanos of Cyrene, but very little is known about either Callixenos or Philostephanos. Fortunately, however, Callixenos gives details about the size of the forty-banker, the length of her longest oars, and the number of her crew, which enables us to gauge his value as an authority, and to pronounce his story to be incredible (see p. 45).

Whatever the arrangement of their oars may have been, these many-banked ships appear to have been large and unmanageable, and they finally went out of fashion in the year 31 B.C., when Augustus defeated the combined fleets of Antony and Cleopatra at the battle of Actium. The vessels which composed the latter fleets were of the many-banked order, while Augustus had adopted the swift, low, and handy galleys of the Liburni, who were a seafaring and piratical people from Illyria on the Adriatic coast. Their vessels were originally single-bankers, but afterwards it is said that two banks were adopted. This statement is borne out by the evidence of Trajan's Column, all the galleys represented on it, with the exception of one, being biremes.

Augustus gained the victory at Actium largely owing to the handiness of his Liburnian galleys, and, in consequence, this type was henceforward adopted for Roman warships, and ships of many banks were no longer built. The very word "trireme" came to signify a warship, without reference to the number of banks of oars.

After the Romans had completed the conquest of the nations bordering on the Mediterranean, naval war ceased for a time, and the fighting navy of Rome declined in importance. It was not till the establishment of the Vandal kingdom in Africa under Genseric that a revival in naval warfare on a large scale took place. No changes in the system of marine architecture are recorded during all these ages. The galley, considerably modified in later times, continued to be the principal type of warship in the Mediterranean till about the sixteenth century of our era.

ANCIENT MERCHANT-SHIPS.

Little accurate information as we possess about the warships of the ancients, we know still less of their merchant-vessels and transports. They were unquestionably much broader, relatively, and fuller than the galleys; for, whereas the length of the latter class was often eight to ten times the beam, the merchant-ships were rarely longer than three or four times their beam. Nothing is known of the nature of Phoenician merchant-vessels. Fig. 12 is an illustration of an Athenian merchant-ship of about 500 B.C. It is taken from the same painted vase as the galley shown on Fig. 9. If the illustration can be relied on, it shows that these early Greek sailing-ships were not only relatively short, but very deep. The forefoot and dead wood aft appear to have been cut away to an extraordinary extent, probably for the purpose of increasing the handiness. The rigging was of the type which was practically universal in ancient ships.

We know from St. Paul's experiences, as described in the Acts of the Apostles, that Mediterranean merchant-ships must often have been of considerable size, and that they were capable of going through very stormy voyages. St. Paul's ship contained a grain cargo, and carried 276 human beings.

In the merchant-ships oars were only used as an auxiliary means of propulsion, the principal reliance being placed on masts and sails. Vessels of widely different sizes were in use, the larger carrying 10,000 talents, or 250 tons of cargo. Sometimes, however, much bigger ships were used. For instance, Pliny mentions a vessel in which the Vatican obelisk and its pedestal, weighing together nearly 500 tons, were brought from Egypt to Italy about the year 50 A.D. It is further stated that this vessel carried an additional cargo of 800 tons of lentils to keep the obelisk from shifting on board.

Lucian, writing in the latter half of the second century A.D., mentions, in one of his Dialogues, the dimensions of a ship which carried corn from Egypt to the Piræus. The figures are: length, 180 ft.; breadth, nearly 50 ft.; depth from deck to bottom of hold, 43-1/2 ft. The latter figure appears to be incredible. The other dimensions are approximately those of the _Royal George_, described on p. 126.

DETAILS OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF GREEK AND ROMAN GALLEYS.

It is only during the present century that we have learned, with any certainty, what the ancient Greek galleys were like. In the year 1834 A.D. it was discovered that a drain at the Piræus had been constructed with a number of slabs bearing inscriptions, which, on examination, turned out to be the inventories of the ancient dockyard of the Piræus. From these inscriptions an account of the Attic triremes has been derived by the German writers Boeckh and Graser. The galleys all appear to have been constructed on much the same model, with interchangeable parts. The dates of the slabs range from 373 to 323 B.C., and the following description must be taken as applying only to galleys built within this period.

The length, exclusive of the beak, or ram, must have been at least 126 ft., the ram having an additional length of 10 ft. The length was, of course, dictated by the maximum number of oars in any one tier, by the space which it was found necessary to leave between each oar, and by the free spaces between the foremost oar and the stem, and the aftermost oar and the stern of the ship. Now, as it appears further on, the maximum number of oars in any tier in a trireme was 62 in the top bank, which gives 31 a side. If we allow only 3 ft. between the oars we must allot at least 90 ft. to the portion of the vessel occupied by the rowers. The free spaces at stem and stern were, according to the representations of those vessels which have come down to us, about 7/24th of the whole; and, if we accept this proportion, the length of a trireme, independently of its beak, would be about 126 ft. 6 in. If the space allotted to each rower be increased, as it may very reasonably be, the total length of the ship would also have to be increased proportionately. Hence it is not surprising that some authorities put the length at over 140 ft. It may be mentioned in corroboration, that the ruins of the Athenian docks at Zea show that they were originally at least 150 ft. long. They were also 19 ft. 5 in. wide. The breadth of a trireme at the water-line, amidships, was about 14 ft., perhaps increasing somewhat higher up, the sides tumbled home above the greatest width. These figures give the width of the hull proper, exclusive of an outrigged gangway, or deck, which, as subsequently explained, was constructed along the sides as a passage for the soldiers and seamen. The draught was from 7 to 8 ft.

Such a vessel carried a crew of from 200 to 225, of whom 174 were rowers, 20 seamen to work the sails, anchors, etc., and the remainder soldiers. Of the rowers, 62 occupied the upper, 58 the middle and 54 the lower tier. Many writers have supposed that each oar was worked by several rowers, as in the galleys of the Middle Ages. This, however, was not the case, for it has been conclusively proved that, in the Greek galleys, up to the class of triremes, at any rate, there was only one man to each oar. For instance, Thucydides, describing the surprise attack intended to be delivered on the Piræus, and actually delivered against the island of Salamis by the Peloponnesians in 429 B.C., relates that the sailors were marched from Corinth to Nisæa, the harbour of Megara, on the Athenian side of the isthmus, in order to launch forty ships which happened to be lying in the docks there, and that _each_ sailor carried his cushion and his oar, with its thong, on his march. We have, moreover, a direct proof of the size of the longest oars used in triremes, for the inventories of the Athenian dockyards expressly state that they were 9-1/2 cubits, or 13 ft. 6 in. in length. The reason why the oars were arranged in tiers, or banks, one above the other was, no doubt, that, in this way, the propelling power could be increased without a corresponding increase in the length of the ships. To make a long sea-going vessel sufficiently strong without a closed upper deck would have severely taxed the skill of the early shipbuilders. Moreover, long vessels would have been very difficult to manoeuvre, and in the Greek mode of fighting, ramming being one of the chief modes of offence, facility in manoeuvring was of prime importance. The rowers on each side sat in the same vertical longitudinal plane, and consequently the length of the inboard portions of the oars varied according as the curve of the vessel's side approached or receded from this vertical plane. The seats occupied by the rowers in the successive tiers were arranged one above the other in oblique lines sloping upwards towards the stem, as shown in Figs. 14 and 15. The vertical distance between the seats was about 2 ft. The horizontal gap between the benches in each tier was about 3 ft. The seats were some 9 in. wide, and foot-supports were fixed to each for the use of the rower next above and behind. The oars were so arranged that the blades in each tier all struck the water in the same fore and aft line. The lower oar-ports were about 3 ft., the middle 4-1/4 ft., and the upper 5-1/2 ft., above the water. The water was prevented from entering the ports by means of leather bags fastened round the oars and to the sides of the oar-ports. The upper oars were about 14 ft. long, the middle 10 ft., and the lower 7-1/2 ft., and in addition to these there were a few extra oars which were occasionally worked from the platform, or deck, above the upper tier, probably by the seamen and soldiers when they were not otherwise occupied. The benches for the rowers extended from the sides to timber supports, inboard, arranged in vertical planes fore and aft. There were two sets of these timbers, one belonging to each side of the ship, and separated by a space of 7 ft. These timbers also connected the upper and lower decks together. The latter was about 1 ft. above the water-line. Below the lower deck was the hold which contained the ballast, and in which the apparatus for baling was fixed.

In addition to oars, sails were used as a means of propulsion whenever the wind was favourable, but not in action.

The Athenian galleys had, at first, one mast, but afterwards, it is thought, two were used. The mainmast was furnished with a yard and square sail.

The upper deck, which was the fighting-platform previously mentioned, was originally a flying structure, and, perhaps, did not occupy the full width of the vessel amidships. At the bow, however, it was connected by planking with the sides of the ship, so as to form a closed-in space, or forecastle. This forecastle would doubtless have proved of great use in keeping the ship dry during rough weather, and probably suggested ultimately the closed decking of the whole of the ship. There is no record of when this feature, which was general in ancient Egyptian vessels, was introduced into Greek galleys. It was certainly in use in the Roman warships about the commencement of the Christian era, for there is in the Vatican a relief of about the date 50 A.D. from the Temple of Fortune at Præneste, which represents part of a bireme, in which the rowers are all below a closed deck, on which the soldiers are standing.

In addition to the fighting-deck proper there were the two side platforms, or gangways, already alluded to, which were carried right round the outside of the vessel on about the same level as the benches of the upper tier of rowers. These platforms projected about 18 to 24 in. beyond the sides of the hull, and were supported on brackets. Like the flying deck, these passages were intended for the accommodation of the soldiers and sailors, who could, by means of them, move freely round the vessel without interfering with the rowers. They were frequently fenced in with stout planking on the outside, so as to protect the soldiers. They do not appear to have been used on galleys of the earliest period.

We have no direct evidence as to the dimensions of ships of four and five banks. Polybios tells us that the crew of a Roman quinquereme in the first Carthaginian War, at a battle fought in 256 B.C., numbered 300, in addition to 120 soldiers. Now, the number 300 can be obtained by adding two banks of respectively 64 and 62 rowers to the 172 of the trireme. We may, perhaps, infer that the quinquereme of that time was a little longer than the trireme, and had about 3 ft. more freeboard, this being the additional height required to accommodate two extra banks of oars. Three hundred years later than the above-mentioned date Pliny tells us that this type of galley carried 400 rowers.

We know no detailed particulars of vessels having a greater number of banks than five till we get to the alleged forty-banker of Ptolemy Philopater. Of this ship Callixenos gives the following particulars:--Her dimensions were: length, 420 ft.; breadth, 57 ft.; draught, under 6 ft.; height of stern ornament above water-line, 79 ft. 6 in.; height of stem ornament, 72 ft.; length of the longest oars, 57 ft. The oars were stated to have been weighted with lead inboard, so as to balance the great overhanging length. The number of the rowers was 4,000, and of the remainder of the crew 3,500, making a total of 7,500 men, for whom, we are asked to believe, accommodation was found on a vessel of the dimensions given. This last statement is quite sufficient to utterly discredit the whole story, as it implies that each man had a cubic space of only about 130 ft. to live in, and that, too, in the climate of Egypt. Moreover, if we look into the question of the oars we shall see that the dimensions given are absolutely impossible--that is to say, if we make the usual assumption that the banks were successive horizontal tiers of oars placed one above the other. There were said to have been forty banks. Now, the smallest distance, vertically, between two successive banks, if the oar-ports were arranged as in Fig. 14, with the object of economizing space in the vertical direction to the greatest possible degree, would be 1 ft. 3 in. If the lowest oar-ports were 3 ft. above the water, and the topmost bank were worked on the gunwale, we should require, to accommodate forty banks, a height of side equal to 39 ft. × 1 ft. 3 in. + 3 ft. = 51 ft. 9 in. Now, if the inboard portion of the 57 ft. oar were only one-fourth of the whole length, or 14 ft. 3 in., this would leave 57 ft. - 14 ft. 3 in. = 42 ft. 9 in. for the outboard portion, and as the height of gunwale on which this particular length of oar was worked must have been, as shown above, 51 ft. 9 in. above the water, it is evident that the outboard portion of the oar could not be made to touch the water at all. Also, if we consider the conditions of structural strength of the side of a ship honeycombed with oar-ports, and standing to the enormous height of 51 ft. 9 in. above the water-line, it is evident that, in order to be secure, it would require to be supported by numerous tiers of transverse horizontal beams, similar to deck-beams, running from side to side. The planes of these tiers would intersect the inboard portions of many of the tiers of oars, and consequently prevent these latter from being fitted at all.

If we look at the matter from another point of view we shall meet with equally absurd results. The oars in the upper banks of Athenian triremes are known to have been about 14 ft. in length. Underneath them, were, of course, two other banks. If, now, we assume that the upper bank tholes were 5 ft. 6 in.[10] above the water-line, and that one-quarter of the length of the upper bank oars was inboard, and if we add thirty-seven additional banks parallel to the first bank, so as to make forty in all, simple proportion will show us that the outboard portion of the oars of the uppermost bank must have been just under 99 ft. long and the total length of each, if we assume, as before, that one quarter of it was inboard, would be 132 ft., instead of the 57 ft. given by Callixenos. Any variations in the above assumptions, consistent with possibilities, would only have the effect of bringing the oars out still longer. We are therefore driven to conclude, either that the account given by Callixenos was grossly inaccurate, or else that the Greek word, [Greek: tessarakontêrês], which we translate by "forty-banked ship," did not imply that there were forty horizontal _superimposed_ tiers of oars.

The exact arrangement of the oars in the larger classes of galleys has always been a puzzle, and has formed the subject of much controversy amongst modern writers on naval architecture. The vessels were distinguished, according to the numbers of the banks of oars, as uniremes, biremes, triremes, quadriremes, etc., up to ships like the great galley of Ptolemy Philopater, which was said to have had forty banks. Now, the difficulty is to know what is meant by a bank of oars. It was formerly assumed that the term referred to the horizontal tiers of oars placed one above the other; but it can easily be proved, by attempting to draw the galleys with the oars and rowers in place, that it would be very difficult to accommodate as many as five horizontal banks and absolutely impossible to find room for more than seven. Not only would the space within the hull of the ship be totally insufficient for the rowers, but the length of the upper tiers of oars would be so great that they would be unmanageable, and that of the lower tiers so small that they would be inefficient. The details given by ancient writers throw very little light upon this difficult subject. Some authors have stated that there was only one man to each oar, and we now know that this was the case with the smaller classes of vessels, say, up to those provided with three, or four, to five banks of oars; but it is extremely improbable that the oars of the larger classes could have been so worked. The oars of modern Venetian galleys were each manned by five rowers. It is impossible in this work to examine closely into all the rival theories as to what constituted a bank of oars. It seems improbable, for reasons before stated, that any vessel could have had more than five horizontal tiers. It is certain also that, in order to find room for the rowers to work above each other in these tiers, the oar-ports must have been placed, not vertically above each other, but in oblique rows, as represented in Fig. 14. It is considered by Mr. W. S. Lindsay, in his "History of Merchant Shipping and Ancient Commerce," that each of the oblique rows of oars, thus arranged, may have formed the tier referred to in the designation of the class of the vessel, for vessels larger than quinqueremes. If this were so, there would then be no difficulty in conceiving the possibility of constructing galleys with even as many as forty tiers of oars like the huge alleged galley of Ptolemy Philopater. Fig. 15 represents the disposition of the oar-ports according to this theory for an octoreme.

It appears to be certain that the oars were not very advantageously arranged, or proportioned, in the old Greek galleys, or even in the Roman galleys, till the time of the early Cæsars, for we read that the average speed of the Athenian triremes was 200 stadia in the day. If the stadium were equal in length to a furlong, and the working day supposed to be limited to ten hours, this would correspond to a speed of only two and a half miles an hour. The lengths of the oars in the Athenian triremes have been already given (p. 42); even those of the upper banks were extremely short--only, in fact, about a foot longer than those used in modern 8-oared racing boats. On account of their shortness and the height above the water at which they were worked, the angle which the oars made with the water was very steep and consequently disadvantageous. In the case of the Athenian triremes, this angle must have been about 23.5°. This statement is confirmed by all the paintings and sculptures which have come down to us. It is proved equally by the painting of an Athenian bireme of 500 B.C. shown in Fig. 9, and by the Roman trireme, founded on the sculptures of Trajan's Column of about 110 A.D., shown in Fig. 16.[11] In fact, it is evident that the ancients, before the time of the introduction of the Liburnian galley, did not understand the art of rowing as we do to-day. The celebrated Liburnian galleys, which were first used by the Romans, for war purposes, at the battle of Actium under Augustus Cæsar, were said to have had a speed of four times that of the old triremes. The modern galleys used in the Mediterranean in the seventeenth century are said to have occasionally made the passage from Naples to Palermo in seventeen hours. This is equivalent to an average speed of between 11 and 12 miles per hour.

The timber used by the ancient races on the shores of the Mediterranean in the construction of their ships appears to have been chiefly fir and oak; but, in addition to these, many other varieties, such as pitch pine, elm, cedar, chestnut, ilex, or evergreen oak, ash, and alder, and even orange wood, appear to have been tried from time to time. They do not seem to have understood the virtue of using seasoned timber, for we read in ancient history of fleets having been completed ready for sea in incredibly short periods after the felling of the trees. Thus, the Romans are said to have built and equipped a fleet of 220 vessels in 45 days for the purpose of resisting the attacks of Hiero, King of Syracuse. In the second Punic War Scipio put to sea with a fleet which was stated to have been completed in forty days from the time the timber was felled. On the other hand, the ancients believed in all sorts of absurd rules as to the proper day of the moon on which to fell trees for shipbuilding purposes, and also as to the quarter from which the wind should blow, and so forth. Thus, Hesiod states that timber should only be cut on the seventeenth day of the moon's age, because the sap, which is the great cause of early decay, would then be sunk, the moon being on the wane. Others extend the time from the fifteenth to the twenty-third day of the moon, and appeal with confidence to the experience of all artificers to prove that timber cut at any other period becomes rapidly worm-eaten and rotten. Some, again, asserted that if felled on the day of the new moon the timber would be incorruptible, while others prescribed a different quarter from which the wind should blow for every season of the year. Probably on account of the ease with which it was worked, fir stood in high repute as a material for shipbuilding.

The structure of the hulls of ancient ships was not dissimilar in its main features to that of modern wooden vessels. The very earliest types were probably without external keels. As the practice of naval architecture advanced, keels were introduced, and served the double purpose of a foundation for the framing of the hull and of preventing the vessel from making leeway in a wind. Below the keel proper was a false keel, which was useful when vessels were hauled up on shore, and above the keelson was an upper false keel, into which the masts were stepped. The stem formed an angle of about 70° with the water-line, and its junction with the keel was strengthened by a stout knee-piece. The design of the stem above water was often highly ornate. The stern generally rose in a graceful curve, and was also lavishly ornamented. Fig. 18 gives some illustrations of the highly ornamented extremities of the stern and prow of Roman galleys. These show what considerable pains the ancients bestowed on the decoration of their vessels. There was no rudder-post, the steering having been effected by means of special oars, as in the early Egyptian vessels. Into the keel were notched the floor timbers, and the heads of these latter were bound together by the keelson, or inner keel. Beams connected the top timbers of the opposite branches of the ribs and formed the support for the deck. The planking was put on at right angles to the frames, the butting ends of the planks being connected by dovetails. The skin of the ship was strengthened, in the Athenian galleys, by means of stout planks, or waling-pieces, carried horizontally round the ship, each pair meeting together in front of the stem, where they formed the foundations for the beaks, or rams. The hulls were further strengthened by means of girding-cables, also carried horizontally round the hull, in the angles formed by the projection of the waling-pieces beyond the skin. These cables passed through an eye-hole at the stem, and were tightened up at the stern by means of levers. It is supposed that they were of use in holding the ship together under the shock of ramming. The hull was made water-tight by caulking the seams of the planking. Originally this was accomplished with a paste formed of ground sea-shells and water. This paste, however, not having much cohesion, was liable to crack and fall out when the vessel strained. A slight improvement was made when the shells were calcined and turned into lime. Pitch and wax were also employed, but were eventually superseded by the use of flax, which was driven in between the seams. Flax was certainly used for caulking in the time of Alexander the Great, and a similar material has continued to be employed for this purpose down to the present day. In addition to caulking the seams, it was also customary to coat over the bottom with pitch, and the Romans, at any rate, used sometimes to sheath their galleys with sheet lead fastened to the planking with copper nails. This was proved by the discovery of one of Trajan's galleys in Lake Riccio after it had been submerged for over thirteen centuries.

The bows of the ancient war galleys were so constructed as to act as rams. The ram was made of hard timber projecting beyond the line of the bow, between it and the forefoot. It was usually made of oak, elm, or ash, even when all the rest of the hull was constructed of soft timber. In later times it was sheathed with, or even made entirely of, bronze. It was often highly ornamented, either with a carved head of a ram or some other animal, as shown in Figs. 8 to 11; sometimes swords or spear-heads were added, as shown in Figs. 19 and 20. A relic of this ancient custom is found to this day in the ornamentation of the prows of the Venetian gondolas. Originally the ram, or rostrum, was visible above the water-line, but it was afterwards found to be far more effective when wholly immersed. In addition to the rams there were side projections, or catheads, above water near the bow. The ram was used for sinking the opposing vessels by penetrating their hulls, and the catheads for shattering their oars when sheering up suddenly alongside. Roman galleys were fitted with castles, or turrets, in which were placed fighting men and various engines of destruction. They were frequently temporary structures, sometimes consisting of little more than a protected platform, mounted on scaffolding, which could be easily taken down and stowed away. The use of these structures was continued till far into the Middle Ages.

As accessed via Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/33098

CHAPTER II.

ANCIENT SHIPS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN AND RED SEAS.

It is not difficult to imagine how mankind first conceived the idea of making use of floating structures to enable him to traverse stretches of water. The trunk of a tree floating down a river may have given him his first notions. He would not be long in discovering that the tree could support more than its own weight without sinking. From the single trunk to a raft, formed of several stems lashed together, the step would not be a long one. Similarly, once it was noticed that a trunk, or log, could carry more than its own weight and float, the idea would naturally soon occur to any one to diminish the inherent weight of the log by hollowing it out and thus increase its carrying capacity; the subsequent improvements of shaping the underwater portion so as to make the elementary boat handy, and to diminish its resistance in the water, and of fitting up the interior so as to give facilities for navigating the vessel and for accommodating in it human beings and goods, would all come by degrees with experience. Even to the present day beautiful specimens exist of such boats, or canoes, admirably formed out of hollowed tree-trunks. They are made by many uncivilized peoples, such as the islanders of the Pacific and some of the tribes of Central Africa. Probably the earliest type of _built-up_ boat was made by stretching skins on a frame. To this class belonged the coracle of the Ancient Britons, which is even now in common use on the Atlantic seaboard of Ireland. The transition from a raft to a flat-bottomed boat was a very obvious improvement, and such vessels were probably the immediate forerunners of ships.

It is usual to refer to Noah's ark as the oldest ship of which there is any authentic record. Since, however, Egypt has been systematically explored, pictures of vessels have been discovered immensely older than the ark--that is to say, if the date usually assigned to the latter (2840 B.C.) can be accepted as approximately correct; and, as we shall see hereafter (p. 25), there are vessels _now in existence in Egypt which were built_ about this very period. The ark was a vessel of such enormous size that the mere fact that it was constructed argues a very advanced knowledge and experience on the part of the contemporaries of Noah. Its dimensions were, according to the biblical version, reckoning the cubit at eighteen inches; length, 450 feet; breadth, 75 feet; and depth, 45 feet. If very full in form its "registered tonnage" would have been nearly 15,000. According to the earlier Babylonian version, the depth was equal to the breadth, but, unfortunately, the figures of the measurements are not legible.

It has been sometimes suggested that the ark was a huge raft with a superstructure, or house, built on it, of the dimensions given above. There does not, however, appear to be the slightest reason for concurring with this suggestion. On the contrary, the biblical account of the structure of the ark is so detailed, that we have no right to suppose that the description of the most important part of it, the supposed raft, to which its power of floating would have been due, would have been omitted. Moreover, the whole account reads like the description of a ship-shaped structure.

[…]

SHIPBUILDING IN ANCIENT GREECE AND ROME.

In considering the history of the development of shipbuilding, we cannot fail to be struck with the favourable natural conditions which existed in Greece for the improvement of the art. On the east and west the mainland was bordered by inland seas, studded with islands abounding in harbours. Away to the north-east were other enclosed seas, which tempted the enterprise of the early navigators. One of the cities of Greece proper, Corinth, occupied an absolutely unique position for trade and colonization, situated as it was on a narrow isthmus commanding two seas. The long narrow Gulf of Corinth opening into the Mediterranean, and giving access to the Ionian Islands, must have been a veritable nursery of the art of navigation, for here the early traders could sail for long distances, in easy conditions, without losing sight of land. The Gulf of Ægina and the waters of the Archipelago were equally favourable. The instincts of the people were commercial, and their necessities made them colonizers on a vast scale; moreover, they had at their disposal the experience in the arts of navigation, acquired from time immemorial, by the Egyptians and Phoenicians. Nevertheless, with all these circumstances in their favour, the Greeks, at any rate up to the fourth century B.C., appear to have contributed nothing to the improvement of shipbuilding.[8] The Egyptians and Phoenicians both built triremes as early as 600 B.C., but this class of vessel was quite the exception in the Greek fleets which fought at Salamis 120 years later.

The earliest naval expedition mentioned in Greek history is that of the allied fleets which transported the armies of Hellas to the siege of Troy about the year 1237 B.C. According to the Greek historians, the vessels used were open boats, decks not having been introduced into Greek vessels till a much later period.

The earliest Greek naval battle of which we have any record took place about the year 709 B.C., over 500 years after the expedition to Troy and 1,000 years after the battle depicted in the Temple of Victory at Thebes. It was fought between the Corinthians and their rebellious colonists of Corcyra, now called Corfu.

Some of the naval expeditions recorded in Greek history were conceived on a gigantic scale. The joint fleets of Persia and Phoenicia which attacked and conquered the Greek colonies in Ionia consisted of 600 vessels. This expedition took place in the year 496 B.C. Shortly afterwards the Persian commander-in-chief, Mardonius, collected a much larger fleet for the invasion of Greece itself.

After the death of Cambyses, his successor Xerxes collected a fleet which is stated to have numbered 4,200 vessels, of which 1,200 were triremes. The remainder appears to have been divided into two classes, of which the larger were propelled with twenty-five and the smaller with fifteen oars a-side. This fleet, after many misfortunes at sea, and after gaining a hard-fought victory over the Athenians, was finally destroyed by the united Greek fleet at the ever-famous battle of Salamis. The size of the Persian monarch's fleet was in itself a sufficient proof of the extent of the naval power of the Levantine states; but an equally convincing proof of the maritime power of another Mediterranean state, viz., Carthage, at that early period--about 470 B.C.--is forthcoming. This State equipped a large fleet, consisting of 3,000 ships, against the Greek colonies in Sicily; of these 2,000 were fighting galleys, and the remainder transports on which no less than 300,000 men were embarked. This mighty armada was partly destroyed in a great storm. All the transports were wrecked, and the galleys were attacked and totally destroyed by the fleets of the Greek colonists under Gelon on the very day, according to tradition, on which the Persians were defeated at Salamis. Out of the entire expedition only a few persons returned to Carthage to tell the tale of their disasters.

The foregoing account will serve to give a fair idea of the extent to which shipbuilding was carried on in the Mediterranean in the fifth century before the Christian era.

We have very little knowledge of the nature of Greek vessels previously to 500 B.C. Thucydides says that the ships engaged on the Trojan expedition were without decks.

According to Homer, 1,200 ships were employed, those of the Boeotians having 120 men each, and those of Philoctetes 50 men each. Thucydides also relates that the earliest Hellenic triremes were built at Corinth, and that Ameinocles, a Corinthian naval architect, built four ships for the Samians about 700 B.C.; but triremes did not become common until the time of the Persian War, except in Sicily and Corcyra (Corfu), in which states considerable numbers were in use a little time before the war broke out.

British Museum, which was found at Vulci in Etruria. It is one of the very few representations now in existence of ancient Greek biremes. It gives us far less information than we could wish to have. The vessel has two banks of oars, those of the upper tier passing over the gunwale, and those of the lower passing through oar-ports. Twenty oars are shown by the artist on each side, but this is probably not the exact number used. Unfortunately the rowers of the lower tier are not shown in position. The steering was effected by means of two large oars at the stern, after the manner of those in use in the Egyptian ships previously described. This is proved by another illustration of a bireme on the same vase, in which the steering oars are clearly seen. The vessel had a strongly marked forecastle and a ram fashioned in the shape of a boar's head. It is a curious fact that Herodotus, in his history (Book III.), mentions that the Samian ships carried beaks, formed to resemble the head of a wild boar, and he relates how the Æginetans beat some Samian colonists in a sea-fight off Crete, and sawed off the boar-head beaks from the captured galleys, and deposited them in a temple in Ægina. This sea-fight took place about the same time that the vases were manufactured, from which Figs. 8 and 9 are copied. There was a single mast with a very large yard carrying a square sail. The stays are not shown, but Homer says that the masts of early Greek vessels were stayed fore and aft.

It is impossible to say whether this vessel was decked. According to Thucydides, the ships which the Athenians built at the instigation of Themistocles, and which they used at Salamis, were not fully decked. That Greek galleys were sometimes without decks is proved by Fig. 10, which is a copy of a fragment of a painting of a Greek galley on an Athenian vase now in the British Museum, of the date of about 550 B.C. It is perfectly obvious, from the human figures in the galley, that there was no deck. Not even the forecastle was covered in. The galleys of Figs. 8 and 9 had, unlike the Phoenician bireme of Fig. 7, no fighting-deck for the use of the soldiers. There was also no protection for the upper-tier rowers, and in this respect they were inferior to the Egyptian ship shown in Fig. 6. It is probable that Athenian ships at Salamis also had no fighting, or flying decks for the use of the soldiers; for, according to Thucydides, Gylippos, when exhorting the Syracusans, nearly sixty years later, in 413 B.C., said, "But to them (the Athenians) the employment of troops on deck is a novelty." Against this view, however, it must be stated that there are now in existence at Rome two grotesque pictures of Greek galleys on a painted vase, dating from about 550 B.C., in which the soldiers are clearly depicted standing and fighting upon a flying deck. Moreover, Thucydides, in describing a sea-fight between the Corinthians and the Corcyreans in 432 B.C., mentions that the decks of both fleets were crowded with heavy infantry archers and javelin-men, "for their naval engagements were still of the old clumsy sort." Possibly this last sentence gives us a clue to the explanation of the apparent discrepancy. The Athenians were, as we know, expert tacticians at sea, and adopted the method of ramming hostile ships, instead of lying alongside and leaving the fighting to the troops on board. They may, however, have been forced to revert to the latter method, in order to provide for cases where ramming could not be used; as, for instance, in narrow harbours crowded with shipping, like that of Syracuse.

It is perfectly certain that the Phoenician ships which formed the most important part of the Persian fleet at Salamis carried fighting-decks. We have seen already (p. 28) that they used such decks in the time of Sennacherib, and we have the distinct authority of Herodotus for the statement that they were also employed in the Persian War; for, he relates that Xerxes returned to Asia in a Phoenician ship, and that great danger arose during a storm, the vessel having been top-heavy owing to the deck being crowded with Persian nobles who returned with the king.

In addition to the triremes, of which not a single illustration of earlier date than the Christian era is known to be in existence, both Greeks and Persians, during the wars in the early part of the fifth century B.C., used fifty-oared ships called penteconters, in which the oars were supposed to have been arranged in one tier. About a century and a half after the battle of Salamis, in 330 B.C., the Athenians commenced to build ships with four banks, and five years later they advanced to five banks. This is proved by the extant inventories of the Athenian dockyards. According to Diodoros, they were in use in the Syracusan fleet in 398 B.C. Diodoros, however, died nearly 350 years after this epoch, and his account must, therefore, be received with caution.

The evidence in favour of the existence of galleys having more than five superimposed banks of oars is very slight.

Alexander the Great is said by most of his biographers to have used ships with five banks of oars; but Quintus Curtius states that, in 323 B.C., the Macedonian king built a fleet of seven-banked galleys on the Euphrates. Quintus Curtius is supposed by the best authorities to have lived five centuries after the time of Alexander, and therefore his account of these ships cannot be accepted without question.

It is also related by Diodoros that there were ships of six and seven banks in the fleet of Demetrios Poliorcetes at a battle off Cyprus in 306 B.C., and that Antigonos, the father of Poliorcetes, had ships of eleven and twelve banks. We have seen, however, that Diodoros died about two and a half centuries after this period. Pliny, who lived from 61 to 115 A.D., increases the number of banks in the ships of the opposing fleets at this battle to twelve and fifteen banks respectively. It is impossible to place any confidence in such statements.

Theophrastus, a botanist who died about 288 B.C., and who was therefore a contemporary of Demetrios, mentions in his history of plants that the king built an eleven-banked ship in Cyprus. This is one of the very few contemporary records we possess of the construction of such ships. The question, however, arises, Can a botanist be accepted as an accurate witness in matters relating to shipbuilding? The further question presents itself, What meaning is intended to be conveyed by the terms which we translate as ships of many banks? This question will be reverted to hereafter.

In one other instance a writer cites a document in which one of these many-banked ships is mentioned as having been in existence during his lifetime. The author in question was Polybios, one of the most painstaking and accurate of the ancient historians, who was born between 214 and 204 B.C., and who quotes a treaty between Rome and Macedon concluded in 197 B.C., in which a Macedonian ship of sixteen banks is once mentioned. This ship was brought to the Tiber thirty years later, according to Plutarch and Pliny, who are supposed to have copied a lost account by Polybios. Both Plutarch and Pliny were born more than two centuries after this event. If the alleged account by Polybios had been preserved, it would have been unimpeachable authority on the subject of this vessel, as this writer, who was, about the period in question, an exile in Italy, was tutor in the family of Æmilius Paulus, the Roman general who brought the ship to the Tiber.

The Romans first became a naval power in their wars with the Carthaginians, when the command of the sea became a necessity of their existence. This was about 256 B.C. At that time they knew nothing whatever of shipbuilding, and their early war-vessels were merely copies of those used by the Carthaginians, and these latter were no doubt of the same general type as the Greek galleys. The first Roman fleet appears to have consisted of quinqueremes.

The third century B.C. is said to have been an era of gigantic ships. Ptolemy Philadelphos and Ptolemy Philopater, who reigned over Egypt during the greater part of that century, are alleged to have built a number of galleys ranging from thirteen up to forty banks. The evidence in this case is derived from two unsatisfactory sources. Athenæos and Plutarch quote one Callixenos of Rhodes, and Pliny quotes one Philostephanos of Cyrene, but very little is known about either Callixenos or Philostephanos. Fortunately, however, Callixenos gives details about the size of the forty-banker, the length of her longest oars, and the number of her crew, which enables us to gauge his value as an authority, and to pronounce his story to be incredible (see p. 45).

Whatever the arrangement of their oars may have been, these many-banked ships appear to have been large and unmanageable, and they finally went out of fashion in the year 31 B.C., when Augustus defeated the combined fleets of Antony and Cleopatra at the battle of Actium. The vessels which composed the latter fleets were of the many-banked order, while Augustus had adopted the swift, low, and handy galleys of the Liburni, who were a seafaring and piratical people from Illyria on the Adriatic coast. Their vessels were originally single-bankers, but afterwards it is said that two banks were adopted. This statement is borne out by the evidence of Trajan's Column, all the galleys represented on it, with the exception of one, being biremes.

Augustus gained the victory at Actium largely owing to the handiness of his Liburnian galleys, and, in consequence, this type was henceforward adopted for Roman warships, and ships of many banks were no longer built. The very word "trireme" came to signify a warship, without reference to the number of banks of oars.

After the Romans had completed the conquest of the nations bordering on the Mediterranean, naval war ceased for a time, and the fighting navy of Rome declined in importance. It was not till the establishment of the Vandal kingdom in Africa under Genseric that a revival in naval warfare on a large scale took place. No changes in the system of marine architecture are recorded during all these ages. The galley, considerably modified in later times, continued to be the principal type of warship in the Mediterranean till about the sixteenth century of our era.

ANCIENT MERCHANT-SHIPS.

Little accurate information as we possess about the warships of the ancients, we know still less of their merchant-vessels and transports. They were unquestionably much broader, relatively, and fuller than the galleys; for, whereas the length of the latter class was often eight to ten times the beam, the merchant-ships were rarely longer than three or four times their beam. Nothing is known of the nature of Phoenician merchant-vessels. Fig. 12 is an illustration of an Athenian merchant-ship of about 500 B.C. It is taken from the same painted vase as the galley shown on Fig. 9. If the illustration can be relied on, it shows that these early Greek sailing-ships were not only relatively short, but very deep. The forefoot and dead wood aft appear to have been cut away to an extraordinary extent, probably for the purpose of increasing the handiness. The rigging was of the type which was practically universal in ancient ships.

We know from St. Paul's experiences, as described in the Acts of the Apostles, that Mediterranean merchant-ships must often have been of considerable size, and that they were capable of going through very stormy voyages. St. Paul's ship contained a grain cargo, and carried 276 human beings.

In the merchant-ships oars were only used as an auxiliary means of propulsion, the principal reliance being placed on masts and sails. Vessels of widely different sizes were in use, the larger carrying 10,000 talents, or 250 tons of cargo. Sometimes, however, much bigger ships were used. For instance, Pliny mentions a vessel in which the Vatican obelisk and its pedestal, weighing together nearly 500 tons, were brought from Egypt to Italy about the year 50 A.D. It is further stated that this vessel carried an additional cargo of 800 tons of lentils to keep the obelisk from shifting on board.

Lucian, writing in the latter half of the second century A.D., mentions, in one of his Dialogues, the dimensions of a ship which carried corn from Egypt to the Piræus. The figures are: length, 180 ft.; breadth, nearly 50 ft.; depth from deck to bottom of hold, 43-1/2 ft. The latter figure appears to be incredible. The other dimensions are approximately those of the _Royal George_, described on p. 126.

DETAILS OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF GREEK AND ROMAN GALLEYS.

It is only during the present century that we have learned, with any certainty, what the ancient Greek galleys were like. In the year 1834 A.D. it was discovered that a drain at the Piræus had been constructed with a number of slabs bearing inscriptions, which, on examination, turned out to be the inventories of the ancient dockyard of the Piræus. From these inscriptions an account of the Attic triremes has been derived by the German writers Boeckh and Graser. The galleys all appear to have been constructed on much the same model, with interchangeable parts. The dates of the slabs range from 373 to 323 B.C., and the following description must be taken as applying only to galleys built within this period.

The length, exclusive of the beak, or ram, must have been at least 126 ft., the ram having an additional length of 10 ft. The length was, of course, dictated by the maximum number of oars in any one tier, by the space which it was found necessary to leave between each oar, and by the free spaces between the foremost oar and the stem, and the aftermost oar and the stern of the ship. Now, as it appears further on, the maximum number of oars in any tier in a trireme was 62 in the top bank, which gives 31 a side. If we allow only 3 ft. between the oars we must allot at least 90 ft. to the portion of the vessel occupied by the rowers. The free spaces at stem and stern were, according to the representations of those vessels which have come down to us, about 7/24th of the whole; and, if we accept this proportion, the length of a trireme, independently of its beak, would be about 126 ft. 6 in. If the space allotted to each rower be increased, as it may very reasonably be, the total length of the ship would also have to be increased proportionately. Hence it is not surprising that some authorities put the length at over 140 ft. It may be mentioned in corroboration, that the ruins of the Athenian docks at Zea show that they were originally at least 150 ft. long. They were also 19 ft. 5 in. wide. The breadth of a trireme at the water-line, amidships, was about 14 ft., perhaps increasing somewhat higher up, the sides tumbled home above the greatest width. These figures give the width of the hull proper, exclusive of an outrigged gangway, or deck, which, as subsequently explained, was constructed along the sides as a passage for the soldiers and seamen. The draught was from 7 to 8 ft.

Such a vessel carried a crew of from 200 to 225, of whom 174 were rowers, 20 seamen to work the sails, anchors, etc., and the remainder soldiers. Of the rowers, 62 occupied the upper, 58 the middle and 54 the lower tier. Many writers have supposed that each oar was worked by several rowers, as in the galleys of the Middle Ages. This, however, was not the case, for it has been conclusively proved that, in the Greek galleys, up to the class of triremes, at any rate, there was only one man to each oar. For instance, Thucydides, describing the surprise attack intended to be delivered on the Piræus, and actually delivered against the island of Salamis by the Peloponnesians in 429 B.C., relates that the sailors were marched from Corinth to Nisæa, the harbour of Megara, on the Athenian side of the isthmus, in order to launch forty ships which happened to be lying in the docks there, and that _each_ sailor carried his cushion and his oar, with its thong, on his march. We have, moreover, a direct proof of the size of the longest oars used in triremes, for the inventories of the Athenian dockyards expressly state that they were 9-1/2 cubits, or 13 ft. 6 in. in length. The reason why the oars were arranged in tiers, or banks, one above the other was, no doubt, that, in this way, the propelling power could be increased without a corresponding increase in the length of the ships. To make a long sea-going vessel sufficiently strong without a closed upper deck would have severely taxed the skill of the early shipbuilders. Moreover, long vessels would have been very difficult to manoeuvre, and in the Greek mode of fighting, ramming being one of the chief modes of offence, facility in manoeuvring was of prime importance. The rowers on each side sat in the same vertical longitudinal plane, and consequently the length of the inboard portions of the oars varied according as the curve of the vessel's side approached or receded from this vertical plane. The seats occupied by the rowers in the successive tiers were arranged one above the other in oblique lines sloping upwards towards the stem, as shown in Figs. 14 and 15. The vertical distance between the seats was about 2 ft. The horizontal gap between the benches in each tier was about 3 ft. The seats were some 9 in. wide, and foot-supports were fixed to each for the use of the rower next above and behind. The oars were so arranged that the blades in each tier all struck the water in the same fore and aft line. The lower oar-ports were about 3 ft., the middle 4-1/4 ft., and the upper 5-1/2 ft., above the water. The water was prevented from entering the ports by means of leather bags fastened round the oars and to the sides of the oar-ports. The upper oars were about 14 ft. long, the middle 10 ft., and the lower 7-1/2 ft., and in addition to these there were a few extra oars which were occasionally worked from the platform, or deck, above the upper tier, probably by the seamen and soldiers when they were not otherwise occupied. The benches for the rowers extended from the sides to timber supports, inboard, arranged in vertical planes fore and aft. There were two sets of these timbers, one belonging to each side of the ship, and separated by a space of 7 ft. These timbers also connected the upper and lower decks together. The latter was about 1 ft. above the water-line. Below the lower deck was the hold which contained the ballast, and in which the apparatus for baling was fixed.

In addition to oars, sails were used as a means of propulsion whenever the wind was favourable, but not in action.

The Athenian galleys had, at first, one mast, but afterwards, it is thought, two were used. The mainmast was furnished with a yard and square sail.